Regular readers of Quilas may remember a post of mine from this time last year called Stealth Gentrification. It’s mostly quotations from an essay titled “Stealth Gentrification: Camouflage and Commerce on the Lower East Side”, by Lara Belkind.

She examines the period from 1980–2005, dividing it into three “stages”: 1980–1994; 1995–2002; and 2003–2005. Part 1 focussed on the stage 1. Part 2 will focus on stage 2. Part 3 will focus on stage 3, whenever I get around to it.

I posted Part 1 after the announcement that the bar Max Fish was closing. Max Fish was one of the first LES-gentrifying establishments, and people who claim to oppose gentrification were lamenting its closing. (They’ve since re-opened, after a failed move to Williamsburg.)

There’s something to be said for not being ostentatious, but just as glitter and paint cannot cover up the class struggle, neither can graffiti and riot gates.

So what exactly are they lamenting? Let’s take a look, shall we?

* * *

- The rise of content industries ushered in a new era of hyper-consumerism. In this milieu, bohemian concepts of the “avant-garde,” “underground,” and even “authenticity” were increasingly considered lifestyle options indicative of social identity, rather than political choices. In addition, with the declining importance of large-scale industrial production, cultural intermediaries, often members of urban subcultures, became essential to the search for new niche markets and marketable differences. This process depended on continuous diversification and the discovery of new source material.

It also meant that cultures once thought to be peripheral — including that of the ghetto and the urban disenfranchised — could be appropriated within the culture industry as sources of content.

…

For the owners of these businesses, recycling an existing storefront was generally cheaper than a full renovation; but it was, more importantly, an expression of cultural identity. Most of the new Lower East Side entrepreneurs [There’s that word I told you about! –Q] saw themselves as operating outside mainstream corporate culture, and preserving the built environment was a way to identify themselves as locals. Nonetheless, they consciously engaged in “new-economy” activities, creating and selling trends of cultural consumption, content and hipness.

Denise Carbonell is one such entrepreneur. … She bought a corner building with several units and a storefront, and today she lives in one of the units and rents the others. Originally, she used the storefront as her studio, but in the mid-1990s she transformed it into a retail space to sell her work: retro-futurist clothing, textiles, jewelry and mobiles. The store had once been a men’s clothing store, Louis Zuflacht, which closed in 1964. Making few renovations, Carbonell has been careful to maintain the exterior, occasionally reinforcing unstable portions of the facade and the “Louis Zuflacht” sign while being meticulous not to change its worn appearance. Still, she decided, for instance, to retain its storefront windows, which were covered with a film, yellow with age. Today, no sign indicates her business; one becomes aware of it only as a glimpse through the open door.

…

Joe Manuse is another local merchant. A painter and printmaker who formerly worked in graphic production, he lives around the corner from the low-key, inexpensive cafe he runs with his brother. The pair opened the cafe in 1997, in a well-worn storefront with no sign. Instead, a single scrawl of graffiti on the security grill reads “Lotus Club,” the café’s name. Across the street is the “Poor People in Action of the Lower East Side” community garden, whose members hold their meetings at the Lotus Club. Here, camouflage was employed to attract middle-class hipsters, but it also created a space without overt class associations.

In 1999, [Mary Beth Nelson] and several partners, all from the neighborhood, opened a gourmet restaurant, 71 Clinton Fresh Food. … With her partners, Nelson then opened two more restaurants on Clinton Street: aKa in 2001, and Alias in 2002. Both are aptly named because they preserve the facades of their previous occupants, a ladies’ dress shop and a Puerto Rican diner. Ironically, Alias had already been the name of the Puerto Rican diner. Originally, it had been “Elias Restaurant,” but the prior owner had replaced the “E” with an “A”.

Nelson made minimal changes to these facades, too — and not just because it was cheaper to do so. … Nelson explained the design was based on a “recycling aesthetic — of grafting onto and transforming.” Her intent was to identify the restaurant with the existing character of the neighborhood and create a spot for locals. Besides, she said, camouflage is the “ultimate New York insider” design strategy.

… The expanding economy of the 1990s also shaped the Lower East Side not simply as a place to consume the products and services of new entrepreneurs, but as a cultural space which could be consumed for its atmosphere. The sense of the neighborhood as a cultural destination was greatly assisted by a cluster of fringe storefront theaters and music venues that added to a layered experience of working-class authenticity, counterculture, and urban edge — and by a proliferation of bars, the ultimate purveyors of ambiance.

…

Luna Lounge … preserved the industrial frontage of a defunct Chinese herb warehouse — with no signage, just a large, dark glass window. Arlene Grocery adopted the name and hand-painted sign of the bodega it replaced, and at first might be confused with another bodega down the street with a sign by the same artist.

… [B]ars were some of the most creative businesses employing camouflage to create image and mystique. For example, in the mid-1990s, one owner opened two theme bars, one which recycled a recently defunct beauty shop, and the other a pharmacy. Named Beauty Bar and Barmacy, they are high-kitsch celebrations of a not-so-distant working-class past.

Camouflage could also be used to heighten exclusivity. The Milk & Honey bar is located behind a dilapidated facade disguised as a clothing alteration shop, and it seats only a dozen people. Its address and phone number are kept unlisted, so potential patrons must first obtain these from friends. … Happy Ending, a bar which opened in a Chinese massage parlor shut down by the police. Happy Ending was a euphemism for the “total-release” massage reportedly delivered on the premises, and the bar maintains the awning and frontage of its former occupant, imprinted with Chinese characters. Nothing at all is visible from the street which might reveal its new use. … Though “invisible” to an uninitiated neighborhood resident, the bar is highly visible among global trend-setters. It has an elaborate website and is recommended on a number of Internet culture sites and weblogs [such as] superfuture.com, a site with listings for New York, Tokyo, Sydney, and Shanghai that describes itself as “urban cartography for global shopping experts”.

* * *

These are the small businesses Jeremiah Moss wants to save.

=-=-=-=-=

1Lara Belkind, Stealth Gentrification: Camouflage and Commerce on the Lower East Side, Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, Vol. 21, No. 1 (FALL 2009), pp. 21-36.

1

1

Class Struggle on Avenue A

11 Nov 2013 3 Comments

by shmnyc in Comments, Ideology, New York City Tags: 7-eleven, avenue a, bodegas, east village, evgrieve, gentrification, hi fi bar, lower east side, neighborhoods, new york city, no 7-eleven nyc, petite bourgeois, soda ban, twitter, vandalism, workers

So, 7‑Eleven on Avenue A and 11th Street finally opened for business on October 30, 2013, and in less than a week’s time, “No 7-Eleven NYC” (N7E) began attacking their workers on Twitter:

And from their blog:

The claim that 7-Eleven employees are harassing local businesses comes from one of their supporters: the owner of the Hi-Fi bar, across the street (red highlighting mine):

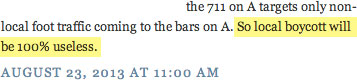

N7E and Co. has never been judicious with the truth. They have attempted to use everything and anything they find as a cudgel against 7-Eleven, from ministers leading campaigns against the store because it sells beer, to claims that 7-Eleven is a “crime magnet” due to the fact that 24-hour 7-Elevens in isolated areas have been robbed, to claims that the city’s attempted soda cap would give 7-Eleven unfair advantage over restaurants and movie theaters! They laud bodegas that over-charge for expired merchandise and make the bulk of their money from selling cigarettes, beer, and lottery tickets in poor neighborhoods.

Yeah, bitch! Bodegas!

It defies reason to accuse the workers of 7-Eleven of this. To begin with, the workers at the new 7-Eleven are new to this hoopla. They haven’t been around since the time of the Hurricane Sandy planning session; they didn’t take the job and immediately join the fray. Secondly, their manager isn’t going to let them leave the store while they’re on the clock, especially to create mischief on the block.

I went into the 7-Eleven yesterday and spoke with a worker there. She told me the story of the owner of Hi-Fi coming in and confronting her. When she told him it wasn’t anyone from there, he became more confrontational. She also told me that most local businesses owners have been very friendly, and wished them well.

Once again, N7E rears its petite-bourgeois head. Attacking big businesses on the one hand, and workers on the other. These are the people who claim the mantle of resistance in the neighborhood.

***

Why would they even make this claim? Apart from the fact that they’ve never bothered with being honest, maybe it’s because this is exactly what they do!

Thursday, Oct 31

Sunday, Nov 3

Monday, Nov 4

EV Grieve reported that someone inside the store revised the N7E skull sign.

Later, he reported that someone outside the store destroyed the revised skull sign.

Friday, Nov 8

The accusations come easily to them because the actions themselves come easily to them.

***

Back in August, in response to the assertion that the 7-Eleven on Avenue A “targets only non-local foot traffic coming to the bars on A,” I responded “It’ll be people in the neighborhood who shop there, watch and see.”

What does N7E say?

I’ve made it a point to pass by there more often recently, to see who is going in, and just as I predicted, it’s neighborhood people. Mostly young mothers and children, mostly Black and Hispanic. In my two times entering the store, and the many times I’ve pass recently, I’ve noticed that the employees are also either Black or Hispanic! Of course, these people are not even on the radar of the all-White N7E!